Last week, Cisco Talos published a blog post with new research on LodaRAT. Apart from updates to the Windows version of this malware, the researchers also found Android malware (‘Loda4Android’) written by the same group. They link both versions of the malware to an ongoing campaign targeting people or entities in Bangladesh.

This blog post reveals some further infrastructure used in this campaign.

LodaRAT

LodaRAT, or Loda, is information gathering malware. It has the ability to take screenshots of infected machines, record keystrokes and sound and allows its operators to send commands to the machine. It was first analysed by Proofpoint in May 2017.

In most of its campaigns, LodaRAT has been spreading through malicious documents, that either contained malicious macros or exploited vulnerabilities in Office. Some earlier campaigns exploited CVE-2017-0199, while more recent ones exploited CVE-2017-11882. Though patched several years ago, the latter vulnerability remains popular among malware authors.

Among the indicators of compromise shared by Talos is the domain lap-top[.]xyz, from which a malicious APK file was served. This domain was registered in October and points to 134.122.120[.]22, an IP address belonging to the popular cloud infrastructure provider Digital Ocean.

While looking in Silent Push’s database for other domains that have pointed to this IP address, Martijn Grooten noticed two that turned out to be actively serving LodaRAT: corona-bd[.]com and imei[.]today.

Using the COVID-19 vaccine as a lure

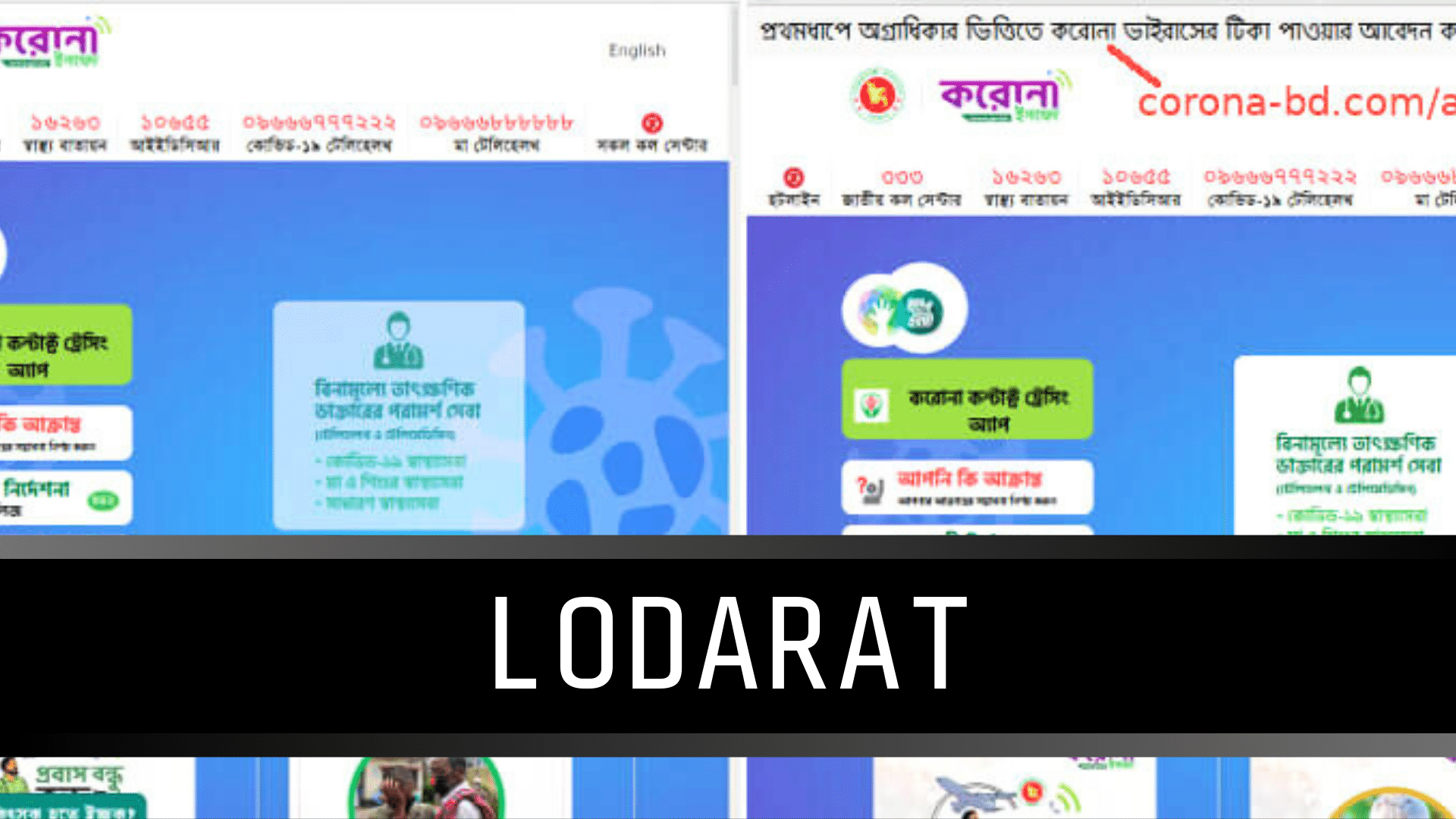

At first glance, corona-bd[.]com looks like an official Bangladeshi government website with information on the coronavirus. That’s not surprising, because in an iframe it contains that very website, hosted at corona.gov.bd.

But right above the iframe, there is a grey bar with the Bengali text “প্রথমধাপে অগ্রাধিকার ভিত্তিতে করোনা ভাইরাসের টিকা পাওয়ার আবেদন করতে এখানে ক্লিক করুন।” which Google helped me translate to “Click here to apply for the corona virus vaccine on a first-come, first-served basis.”

The real Bangladeshi government website (left) and the fake one with an extra link on top (right)

This link goes to a form that asks for many personal details, some of which (such as “Freedom Fighter Status”) may appear unusual for non-Bangladeshis. Upon filling in the form, you are presented with a page telling you your application has been accepted. It is unclear whether the information filled in the form is used in some way, but JavaScript carefully checks you have filled everything in, after which it is submitted to the server in a POST request.

Once you have submitted the form, you are urged to download the a copy of the application. Apart from a receipt number, which is different every time the page loads, you are given a password to open the application. The application turns out to be a zip file protected with this password and inside is a variant of LodaRAT (SHA256: e78546bb33df88c6be3afce32f5d13084295a6e0599b26c3b380d54318170d86).

It is unknown how people end up on this website: whether it relies on natural traffic, or whether the campaign urges specific targets to visit it, but the context of the campaign and the apparent lack of public links to it make the latter more likely.

Interestingly, the domain corona-bd[.]com had been active many years ago, when it hosted the website of a fashion company. Last spring, it was registered again to serve information related to the coronavirus pandemic.

From the copy on the Wayback Machine, Martijn couldn’t determine any malicious purpose of this website, but it shared an IP address with a number of domains that Talos also linked to this campaign, so it is likely that the same actor was hosting it already. This would suggest this campaign, or at least preparations for it, started well before October.

Fake IMEI checker

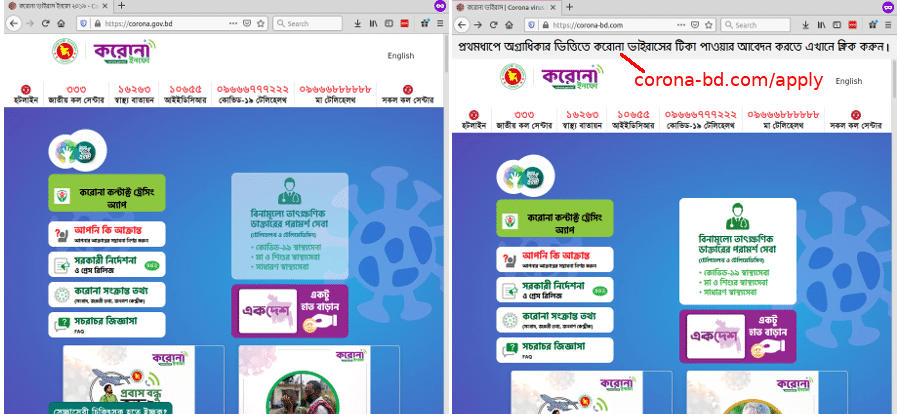

The second domain, imei[.]today, hosts what appears to be a checker for IMEIs: numbers that uniquely identify mobile phones.

The page lay-out is largely copied from the legitimate site imei.info, but made to look to belong to the BTRC, the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission. This site thus too targets Bangladesh, even if it is written in English, a language however still widely understood in the country.

Legitimate (left) and malicitious (right) IMEI checker

Upon entering a valid IMEI number (client-side JavaScript performs the ‘Luhn check’), the user is served a zip file. Inside this zip file, which this time is not protected with a password, is another variant of LodaRAT (SHA256: cf29981bfec0f0cf2abd54ae469c8795a3cf1e19c715ded329fdb2707f982407).

Other domains

While I found these domains because both have used the IP address 134.122.120[.]22, they have in fact shared several more IP addresses. And there are several more domains that have used some of these addresses in recent months.

One is mybnp[.]club. This site looks near identical to bnpbd.org, the website of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (a Bangladeshi political party), from which it includes most content. The only difference is a line on top that says (in Bengali) “Click here to register to become a member of the BNP” that links to a signup page. This signup page contains an iframe that loads content from http://educationboardresults[.]net/php/application/.

However, there is no content there: educationboardresults[.]net is a parked domain. Moreover, mybnp[.]club does not render well in most modern browsers, due to mixed content errors. It may be that this site was intended to be used in the campaign but then abandoned.

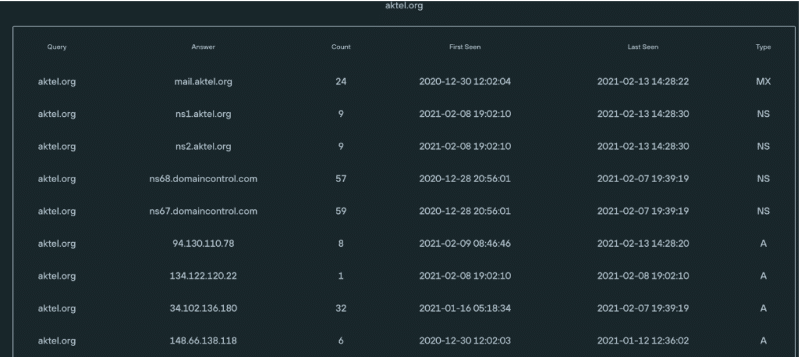

Other domains that have used IP addresses in the same set include av24[.]co and bracbank[.]info, both of which were mentioned by Talos, but also bkash[.]club, bkashagent[.]com, aktel[.] org and zepode[.]online. All of these are relevant to Bangladeshis: bKash is a mobile financial service in Bangladesh, AKTEL is the former name of a mobile phone provider in Bangladesh, and Zepode is an ecommerce platform popular in the region.

Information on aktel[.]org on Silent Push’s dashboard.

Apart from using some of the same IP addresses, all of these domains use two nameservers ns1.domain and ns2.domain with domain the domain itself and both name servers pointing to the same IP address as the domain’s A recor , a somewhat peculiar set-up.

Martijn had not been able to find any content hosted on these latter four domains, but that does not mean URLs with malware don’t exist. It is also possible that these have been registered for future use in this campaign.

A hacker-for hire campaign?

Writing about the discovery of LodaRAT activity in Bangladesh, Cyberscoop suggests it might belong to a hacker-for-hire group.

Last year, several hacker-for-hire operations (sometimes referred to as ‘cyber mercenaries’) have been uncovered. Such groups make cyber-espionage capabilities available to companies, political organisations as well as nation states without their own offensive cyber capabilities.

LodaRAT’s activity has all the hallmarks of such an operation. First, the geographic spread of the activities: Talos believes the group is based in Morocco (which is why it is referred to as ‘Kasablanka’) and previous activity by this group was linked to Latin America, while this campaign targets Bangladesh. The Android malware used by this group has been linked to campaigns in the Middle East.

Secondly, the malware focuses on gathering information rather than on direct financial gain, which would be common for malware used by a more traditional cybercrime group.

And thirdly, this particular campaign appears fairly targeted. While the real size can’t be determined without global telemetry, a more widespread campaign would have likely left public traces through search engines and public thread feeds.

Of course, none of this is conclusive proof of the kind of operation this is. Nor does it mean that the authors of the malware are the same as the ones conducting this campaign.

Conclusion

Malware and phishing campaigns make a serious effort to stay under the radar. However, limited resources forces threat actors to reuse infrastructure.

In this case, with the Silent Push API, Martijn was able to use this weakness to uncover more infrastructure used by the ‘Kasablanka’ actor in its targeting of Bangladesh, based on a few publicly posted indicators.

With contributions from Ken Bagnall and Nick Kostopoulos.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

Domain names:

aktel[.]org

bkashagent[.]com

bkash[.]club

corona-bd[.]com

imei[.]today

mybnp[.]club

zepode[.]online

Also likely linked to this campaign because of shared infrastructure and similar set up, but with no apparent Bangladesh link:

c0mputer[.]xyz

piramidewebs[.]com

IP addresses:

94.130.110[.]78

107.180.72[.]97

107.180.73[.]34

107.180.73[.]135

116.203.37[.]39

134.122.120[.]22

Of these, 94.130.110[.]78 had a PTR record set to be vps.corona-bd[.]com, while 134.122.120[.]22 used vps.lap-top[.]xyz as a PTR record. This confirms that at least these two IP addresses are or were attacker owned rather than shared hosting space.

Some other IP addresses that the domains have pointed to were shared with too many unrelated domains to considered them reliable indicators for this domain, or for malicious activity in general; hence they have not been listed.

SHA256 hashes of LodaRAT variants:

cf29981bfec0f0cf2abd54ae469c8795a3cf1e19c715ded329fdb2707f982407

e78546bb33df88c6be3afce32f5d13084295a6e0599b26c3b380d54318170d86